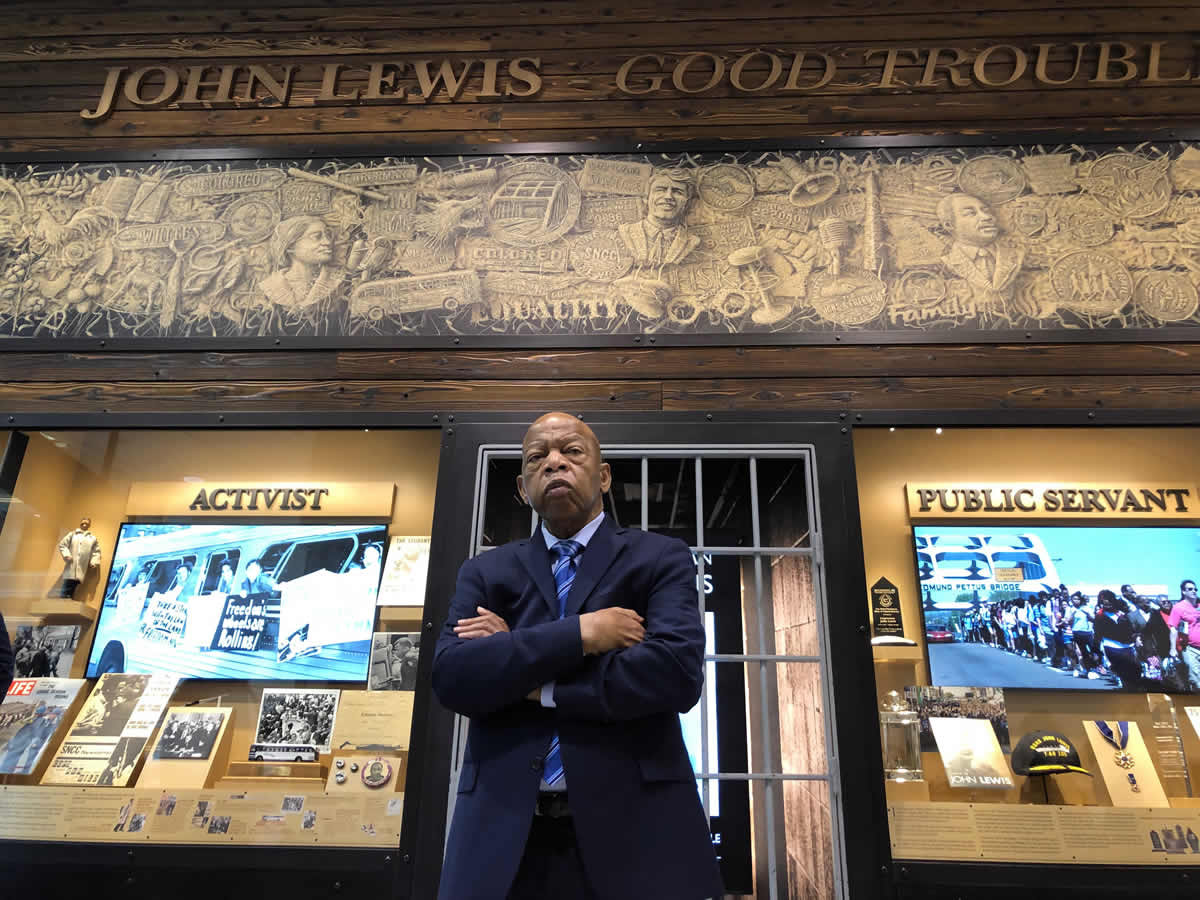

John Lewis: Good Trouble

By Dorothy Reed

SF/Arts Speaks With Bay Area Director Dawn Porter

Sheryll Cashin is a Race and American Law professor at Georgetown University Law School who, like Congressman John Lewis, was born and reared in Alabama. Like Lewis, her father was a civil rights activist, a story she details in The Advocate's Daughter, one of several books she's written on race relations. We asked her opinion of Lewis. She paused and then said with the utmost reverence, 'He's saintly.'

John Lewis: Good Trouble, a well-researched, 96-minute documentary by award-winning San Francisco-African-American director Dawn Porter provides ample evidence to substantiate that observation for those who only know Lewis as the man who had his skull cracked by police on the Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

Here is lifelong portrait, public and private. We see Lewis as a little boy enlisting his older brother to pick cotton for him so that he could go to school, which he did with a bible in hand, dressed in shirt and tie. He practiced preaching and speechifying to the chickens in his yard, foreshadowing a long career inspiring audiences to take political action. As a teenager he joined Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at King's request and expense, even though his family had warned him, 'Don't get in trouble.' But trouble, 'good trouble,' as he called it, was just what Lewis wanted. It was the beginning of a lifelong struggle for justice and full enfranchisement.

In the documentary, Lewis says he was arrested 40 times during the 1960s and five times since coming to Congress. He was Chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; a key participant and youngest speaker at the March on Washington; and an organizer in Mississippi during the bloody voter registration drive in the summer of 1964 - and bloody it was. Later, he would receive his B.A. in Religion and Philosophy, marry Lillian Riles, a union that would last 44 years until her death. His legislative life began in 1981 when he was elected to the Atlanta City Council and in 1986 he won a bitterly contested race against his friend Julian Bond for a Congressional seat. He's held that seat ever since, has been a consistent advocate for progressive legislation, especially ensuring voting rights. He has been called 'the conscience of Congress.'

The documentary's greatest strength is in showing rather than telling us all that history. Lewis has lived his public life largely in front of news cameras. Archivist Rich Remsberg had a huge job combing through all of the available material, and Porter says when they showed Lewis some of their findings, he was astounded. That confrontation with his past provides someone of the most dramatic moments of the film.

The documentary is rich with testimonials from former presidents, colleagues, staff, family and even ordinary people in airports and on the hustings. We see Lewis, a man comfortable in his own skin, joking with his chief of staff, as he energetically bounds steps like a man half his age. We also catch a glimpse in private moments of him at his homes in Washington, D.C. and Atlanta. We learn that he's a lover and collector of art, including ceramic chickens. In case you didn't know legislation to build the National Museum of African American History and Culture was introduced by Congressman Lewis and Congressman Mickey Leland in 1988. And then there's the John Lewis who loves to dance, and, yes, he has the moves. This treatment, this praisesong for a hero, is well-deserved. The 80-year-old congressman is now battling cancer. When he announced his Stage 4 pancreatic cancer diagnosis at the end of last year, he noted he had been told he has a 'fighting chance,' adding, 'We still have many bridges to cross.'

One of those bridges is voter suppression. In a scene where he is stumping for Stacey Abrams during her failed 2018 bid for governor of Georgia, Lewis intones, 'The vote is still the most powerful, non-violent tool we have in a democratic society.' Former Attorney General Eric Holder emphasizes that voting rights is 'the work that John Lewis has stood for all of his life.' Holder warns that the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby v. Holder has made it 'more difficult for people to vote.'

With the upcoming consequential November presidential election, this film clearly was meant to be a call to arms. Congressman Lewis states several times that he believes our democracy is under threat and that preserving the right to vote and exercising that right is crucial. John Lewis: Good Trouble was an Official Selection at the prestigious New York-based Tribeca Film Festival. It was scheduled to have its world premiere there in April. But April in New York was no place for gatherings. Because of Covid-19, the festival has been indefinitely postponed. Instead of New York, the documentary premiered in Tulsa, Oklahoma on June 19 as part of Juneteenth, a celebration of freedom from slavery, the night before President Trump's rally, and, as Porter said, it was a 'planned rebuke' to the campaign appearance. That seems only fitting. A documentary about John Lewis ought to be used as a political tool in America's continuing battle against forces determined to setback racial progress.

Porter worked with producer Laura Michalchyshwn on the documentary which was two years in the making. The two previously worked together on the acclaimed docuseries Bobby Kennedy for President. The Lewis project was actually presented to them by CNN Films executives Amy Entelis and Courtney Sexton of award-winning documentary RBG fame. The team was also joined by Los Angeles-based filmmakers Erika Alexander and Ben Arnon who had been planning a Lewis documentary of their own. The team worked with Magnolia Pictures, Participant, CNN Films and AGC Studios.

'John Lewis: Good Trouble.' Check johnlewisgoodtrouble.com for listings.

Interview Between SF/Arts Monthly Contributor Dorothy Reed and 'John Lewis: Good Trouble' Director Dawn Porter

Dorothy Reed (DR): Congratulations! I really liked this film an awful lot. I am a big fan of John Lewis, and I am the daughter of a Civil Rights Movement activist.

So much has happened lately [that's not in the documentary], and I am wondering when did you finish the film?

Dawn Porter (DP): We finished probably November-December last year. Yeah, the world is quite a different place.

DR: He [Congressman John Lewis] didn't know about his cancer diagnosis (Stage IV pancreatic) yet, right?

DP: He did not know about his cancer. We finished the film before that.

DR:: And then we had COVID-19 and then we had George Floyd's killing and Black Lives Matter protests and [Confederate] monuments coming down. Were you tempted to go back for his reflections?

DP: No, I wasn't because I think - you always want to go back - but I wasn't really with this because I really feel like John Lewis's message of participate, be active, be compassionate is timeless. And it's really a message that we need right now.... I hope that after seeing the film, you can know without even asking the question how he would respond today.... When you hear him talk, he says what you would expect. 'I understand frustration, anger and pain. I understand the impulse to lash out, but I believe that lasting change comes from using your voice.' So much history, so much strategy went into securing protections for voter participation and ensuring protections for freedom of speech. This is one area where we see that legacy.We see people and their impulse is to take it to the streets and to march together for the most part peacefully and in solidarity. And that is a direct nod to the Civil Rights era and to that method that was successful. I hope people will continue to protest, but I also hope people will go and vote because I think there's been a lot of hopelessness in recent months and years because of the devastating horror of the Trump presidency. Our hope, our film, is a rebuke to that by saying if you understand your history, you understand there will be dark times, but your job in dark times is to work harder not to go and hide.

DR: I'd like to talk about your style. This [documentary] ... is primarily cinéma vérité, but you did some interesting things. One is the use of [Washington, D.C'] Arena Stage. You open [the documentary] with a blank stage, Lewis sits on a stool, his aide adjusting his tie. It gives it a kind of dramatic feel. It's almost like a dramatic monologue. How did you come to that [choice]?

DP: When you have such an iconic figure, they [the viewers] know the Civil Rights history. They know of that moment on the bridge [the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL where on Bloody Sunday in 1965 Lewis was brutally beaten by police during a peaceful Voting Rights march], and I thought he needs to be the one to tell his story. He needs to be the one that we're hearing from....So, we created all these mini [archival] films... that were made for him.And then we darkened the theater, put him in the middle, and we just had a conversation about what he was seeing. I didn't have to direct him to be so passionate.He was just living it again.So I said, 'How do you feel about your life?' He said, 'I feel lucky, blessed, but there are forces trying to take us back.' So, that is how he began his story.And I just thought what a beautiful frame.

DR: There's another frame though. The frame being that the opening shot is [the lawsuit] Shelby v. Holder [Supreme Court 2013 decision that took the teeth out of the Voting Rights Act].... This film seems to be two stories. There's a real threat to our democracy right now with efforts to suppress the vote.... and there's the John Lewis life story.

DP: That was something I was really interested in exploring.... What is the relevance of a John Lewis today. And what I wanted to kind of explore and demonstrate is everything that John Lewis experienced as a young person led him to these fights today.So these questions are ongoing. Justice is not a place that you arrive at, the last square of a Monopoly game.It is an every living, breathing, evolving concept that must continuously be protected, fought for, discussed.How do you live a just life is what Plato, what all the great philosophers asked. How do you live a just life?And I think that that's a question thatJohn Lewis has been asking himself since he began his activist career more than 60 years ago. So, it is two stories, but I think that they are inextricably intertwined.Our present is so shaped by our past, so how do we not repeat the mistakes of old, how do we move on?

DR: I have to ask you about the very end of your film. After the credits roll, you have him [Lewis] singing Happy [Pharrell Williams's hugely popular 2013 paean to unbridled mirth]. It kind of left me wondering.I guess it's not such a joyous time right now. Why did you put that there?

DP: You know, when we finished, it was a different world. Someone asked me would I change that [ending] now. I have to think about it, but I don't think so because the point of that song is how is Mr. Lewis today. And even with all that he's seen, with all that he's experienced, with all that he's been through, he's a very happy person and I think that he's happy because he lives his life in accordance with his principles because he decided who he wanted to be and he's been that person his entire life. You know and I think that when we are living in such a dark time ... [you ask yourself] can I even be happy in the midst of all of this global disease and all of this racism, this turmoil?And I think Mr. Lewis's answer to all that is, 'Absolutely.' If we do not live our lives with joy, then what is the purpose of life? So, if a person who is as serious ... as Mr. Lewis can also dance ... and collect art, I think part of his message which I don't think people really focus on so much is life is very full and there are many beautiful things and there are terrible things but you can't forget the beautiful things.

DR: One of the most powerful moments in the film for me was listening to Skip Gates [Henry Louis Gates Jr., Harvard professor and host of the PBS series Finding Your Roots] describe showing John Lewis his great-great grandfather's voter registration card.... I'm curious why you didn't show that [card] because I kept wanting to see it.

DP: You wanted to see it.I just was really taken with how Skip told the story. And there is a tradition of storytelling that our historians pass on and so much of what we do as documentarians is we try to find the actual moments, but that moment I thought it was almost as important in the time as it was in the moment, you know. Of all the shows that Skip Gates has done about all of the people and their histories that is something that just came right to mind for him is showing John Lewis his great-great grandfather’s voter registration card. He was just floored by that, that he found that, and I think we all are. For me, seeing how Skip was so moved by that moment, that was what I wanted people to experience. But I can see [your point]. It's a good note. [The episode of Gates with Lewis is from Season 1 of Finding Your Roots, and it's available on Amazon.

DR: I have to talk a little bit about Julian Bond.

DP: Yeah.

[There's a segment in the documentary on Lewis's nasty 1986 Congressional primary run-off campaign against his fellow Civil Rights activist Julian Bond. Their friendship was sorely strained when Lewis put political gain above friendship by announcing he'd taken a drug test, and he challenged Bond to do the same. There were unsubstantiated rumors that Bond was doing drugs. Lewis's challenge incensed and wounded Bond, and Bond lost the election.]

DR: You don't really go into [the question]: Does John Lewis have any regrets about that?

DP: I asked him nine ways til Sunday what he wanted to say about that and he would just say, 'Julian is a great friend and a great leader, and you know at some point it's kind of like pushing your grandmother to tell you the real story. And so, I thought ...I am already like really pushing it by including the story. He knew - because I was asking him about it - that it was in there. But I think it is clear that one of the things that we do with people that we kind of lionize is we idolize them and we think they could never do something that we really disapprove of and that's not fair to any human being. Right? So, I kind of was hoping that the audience could feel the tension while we might disagree with what he did, which, by the way, today is the most mild of political dirty tricks. But while that might take you back a little bit, we all also really understand the importance of John Lewis becoming a legislator.So, you know, how high of a horse can all of us get on? So, I thought it was interesting because we applaud his persistence and resistance when it's for civil rights, but he kind of went to the mat for himself. In some ways it's really important we give people their full humanity, warts and all.... Nobody's perfect. Not even a John Lewis....Apparently they have made up. Time has healed that wound.

DR: Back to voting... and how important it is in the next election, there's a message here and the group that you want to hear it, I'm sure, is young voters because they are the ones who are going to make a difference, the people who are demonstrating.

DP: I have an 18-year-old and I see the conversations and I see what he is wrestling with. I also see that he is really excited to vote. I think a lot of times we, perhaps, are not paying attention to youth movements. When you think that John Lewis was 19-years-old when he was organizing sit-ins that ultimately led to lasting desegregation, that youth movements have always been at the forefront of social change. So, whether it's the environmental movement that we see today, the anti-gun violence or the civil rights movement, those are people we should pay attention to. And, I, for one, really heartened and I wanted to show people like my son that what you're doing could be really, really important.